Topic

Millions of calculations in overheated offices as a path to green gas

Sulphur hexafluoride (SF6), the holy grail of the power industry, circulates in electricity substations sealed in circuit breakers. It is non-toxic, non-flammable and has perfect insulating properties, thus being capable of interrupting electric current, for example when a switch is flipped. Physicists have spoken of it only in superlatives since it came into use in the first half of the 20th century. Unfortunately, it also comes with negatives. It is unrivalled among greenhouse gases in terms of its harmfulness and it significantly damages the environment. Therefore, scientists, including electrical engineers from the BUT, decided to find a more environmentally friendly replacement.

Petr Kloc welcomes me to his office at the Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Communication. A wave of heat immediately hits my face, even though there are people in coats outside the window and the radiators are off. It raises a question in my mind: is somebody mining Bitcoin here? “They are running the calculations for our project,” laughs the physicist, who is involved in a European project led by the international corporation General Electric.

How can a computer running non-stop help the environment? “Before anything is tested in real life, for example in our case the insulating gas in the circuit breaker, it is tested using numerical models. The better the input data, the more precise the models" describes the role of BUT in the project Petr Kloc, who, in addition to the Department of Power Electrical and Electronic Engineering, works at the CVOOZE workplace at the FEEC BUT. The office machines are tasked with calculating how the Novec g3 gas, which was intended to replace the environmentally unfriendly SF6, behaves at certain temperatures and pressures, the researcher continues: “It seems like it could be a great candidate. It is non-toxic, non-flammable, has better insulation properties than SF6 and is approximately twelve times less environmentally damaging."

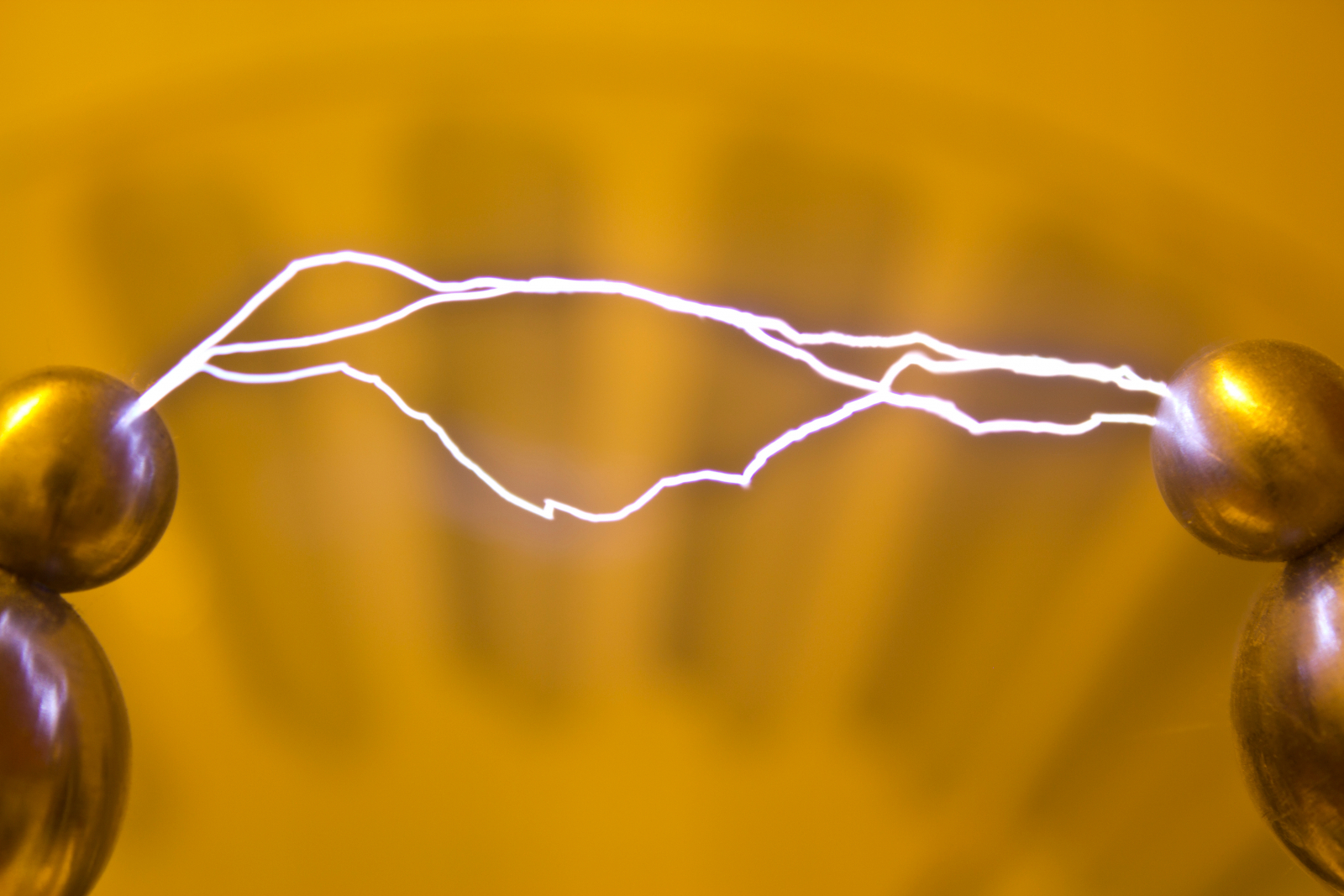

High-voltage substations are currently the only place where SF6, or sulphur hexafluoride, can be used, and that is only because there is no approved replacement for it yet. “When you need to break an electrical circuit, for example when you want to turn off a device with a switch or when fault occurs, you put the contacts apart. But the moment you do that, an electric arc appears between them, still carrying current. The same arc is used, for example, in welding,” explains Petr Kloc and adds that in order to break this electric arc, in the case of substations, the contacts would need to be separated by tens of metres. However, nobody wants such large machines, and this is the moment where the SF6 gas shines; it is pumped into the machines themselves. Its excellent insulating properties will extinguish this discharge and instead of a ten-metre building, a two-metre one is enough.

The issue arose when experts came up with the scale of the harmfulness of greenhouse gases. While CO2 was given the value of 1, SF6 took the top spot with a value of 23,500 – a terrible result. Translated into practice, such a figure means that a kilogram of SF6 has the same impact as 23 tonnes of CO2. And that is definitely not good news for our planet.

The Novec g3 gas, which is being researched by electrical engineers at the BUT, is better in almost every respect. Problems could arise when using it in cold climates, as the gas tends to liquefy in such conditions. In such a case, when inspecting an electrical substation in Finland, technicians might find a puddle of insulating gas on the floor inside the device, which would not extinguish any electrical discharge. “That is why this new Novec gas is mixed with CO2. And this is what our project is all about – finding out what properties the gas will have in different ratios. If you put in a lot of Novec, it will be good in terms of electrical properties, but you will not be able to use it in winter; this is solved by CO2, which however worsens the insulation properties,” summarises Kloc, turning back to the computer screen.

The columns show alternating values of pressure, temperature and various chemical elements. It is not possible for a human to calculate all the possibilities and it is not an easy task for computers either, as there are over five million combinations and each one takes five to ten minutes to calculate. An average computer would take about fifty years to finish the task.

“We have two computer rooms with sixty new machines and in the summer, when there were no classes, I took them all and ran calculations on them. However, it happened to me once that an entire classroom was shut down by an under voltage protective device over the weekend. Fourteen days of calculations on thirty computers were gone. I then had to write a programme that monitored the calculations and if needed forwarded the logs to another computer, thus effectively involving the unused devices at our faculty,” concludes Petr Kloc, adding that although General Electric has already presented the first prototype of the g3 gas-filled substation, the calculations will still run for some time at the FEC to create a complete picture of its properties.

(tk)

Antibiotic resistance in the poultry microbiome is investigated by FEEC BUT

Doctors and technicians focus on radiation exposure after a nuclear disaster or the effectiveness of radiotherapy

Greater efficiency and completely new applications. Experts from FEEC BUT also collaborate on satellites for very low orbit

YSpace succeeds in prestigious ESA programme and heads to space

How to care for a greenhouse? In city park Lužánky, they are building an autonomous watering system that will take care of it for you.