Ideas and discoveries

Eclipse expedition: a castway against our will and the sky without a cloud

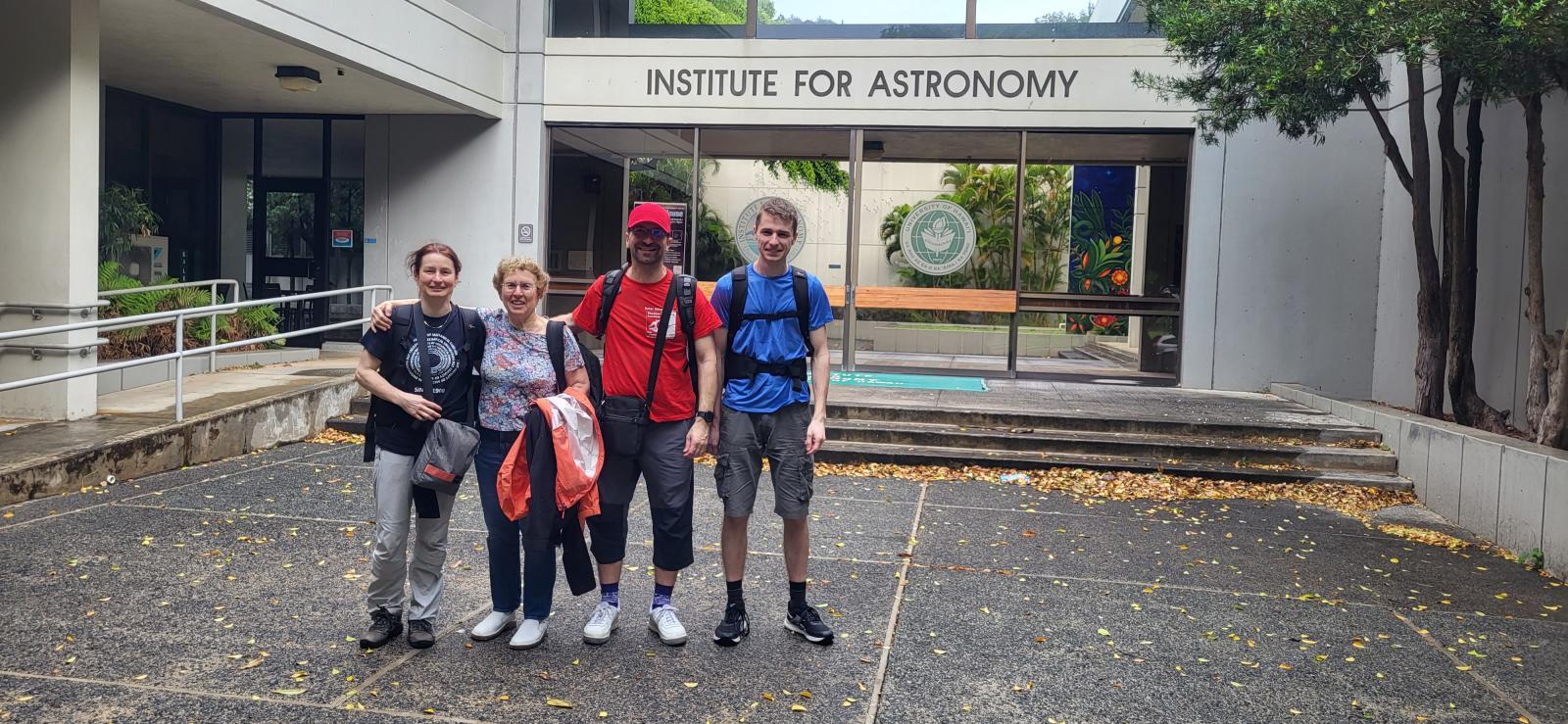

For a fleeting moment, the Moon covers the Sun's disk. Nature falls silent and the world is plunged into darkness... A total solar eclipse is the moment that an international team of mathematicians from the FME (Faculty of Mechanical Engineering) BUT (Brno University of Technology) and representatives from the Astronomical Institute of the University of Hawaii travel around the world to see. They call themselves Solar Wind Sherpas. The next total eclipse will occur on 20 April in the Indian and Pacific Oceans and will be observed by researchers in Australia. The mathematician Jana Hoderová describes how the expedition works in her travel notes.

PART 1 OF THE ECLIPSE EXPEDITION SERIES

Thursday 6 April

From the Czech Republic, we are going on the expedition from the Institute of Mathematics, my colleague Pavel Štarha and I, as well as a student of mechatronics from our faculty Matěj Štarha. Our colleague Miloslav Druckmüller, the author of the famous images of the solar corona, was involved in all the preparations and planning of the experiments, but is not physically participating in the expedition. He'll wait for us to bring him the data to process.

We left Vienna at 9:05 a.m. and landed in Honolulu, Hawaii at 10:00 p.m. the same day, which is only possible due to the time difference of minus 12 hours compared to the Czech Republic, because we spent a total of 18 hours and 25 minutes on the planes.

Friday 7 April

In Honolulu, we start work at 8:00. With it being the Friday before Easter, the building is empty and we can expand into the hallway where we have moved two large tables. This turns out to be a win – firstly, it is not as cold as in the air-conditioned laboratories and workrooms, but furthermore, we are next to a glass wall, so we can see out into the green. In the previous years we worked in a laboratory without windows and you lost track of time. But anyway, the time-shift crisis catches up with us at 14:00 and we hibernate in our chairs for a while. They offer to take us to a hotel, but we refuse because that is not an option.

|

The Solar Wind Sherpas is an international team of scientists who travel the world to observe and collect data on total solar eclipses. The team, aptly named given the vast amount of equipment they bring with them to each (usually remote) observing site, is led by Shadia Habbal of the Hawaii Institute of Astronomy in Honolulu. So far, Solar Wind Sherpas have made 14 eclipse expeditions, including to India (1995), Syria (1999), Libya (2006), China (2008), the Arctic (2015) and Indonesia (2016). The team is one of the few in the world to have exploited the diagnostic potential of coronal emission line observations at multiple wavelengths, leading to a number of discoveries and successful scientific publications. Researchers are also studying the invisible “colours” of the Sun's corona. With their cameras equipped with special filters and their own spectrometer design, they observe the behaviour of elements that have lost most of their electrons and emit light in very specific colours. The most dominant elements include hydrogen, helium, iron, nickel, oxygen, carbon and calcium. Each of them holds the secret of the hot corona that escapes from the Sun and forms the solar wind. |

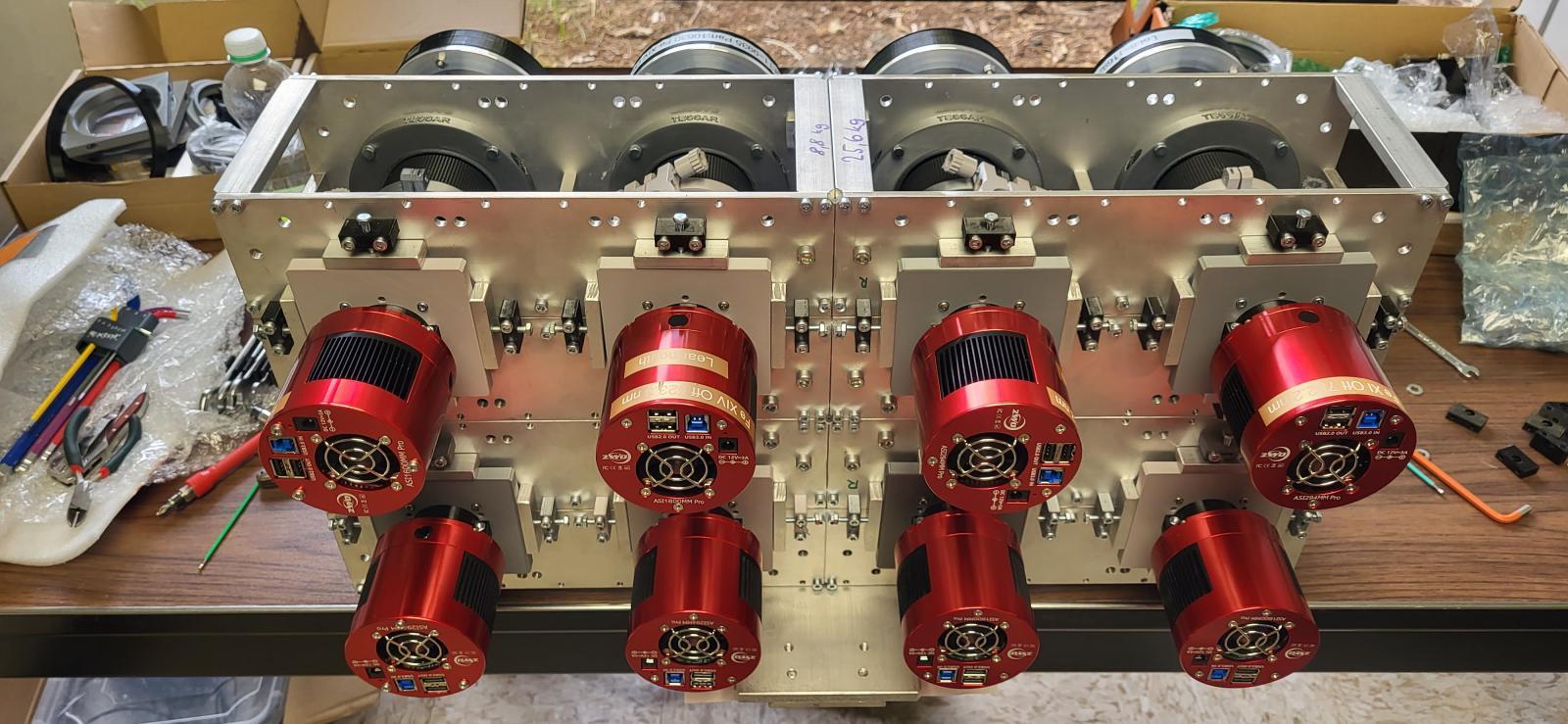

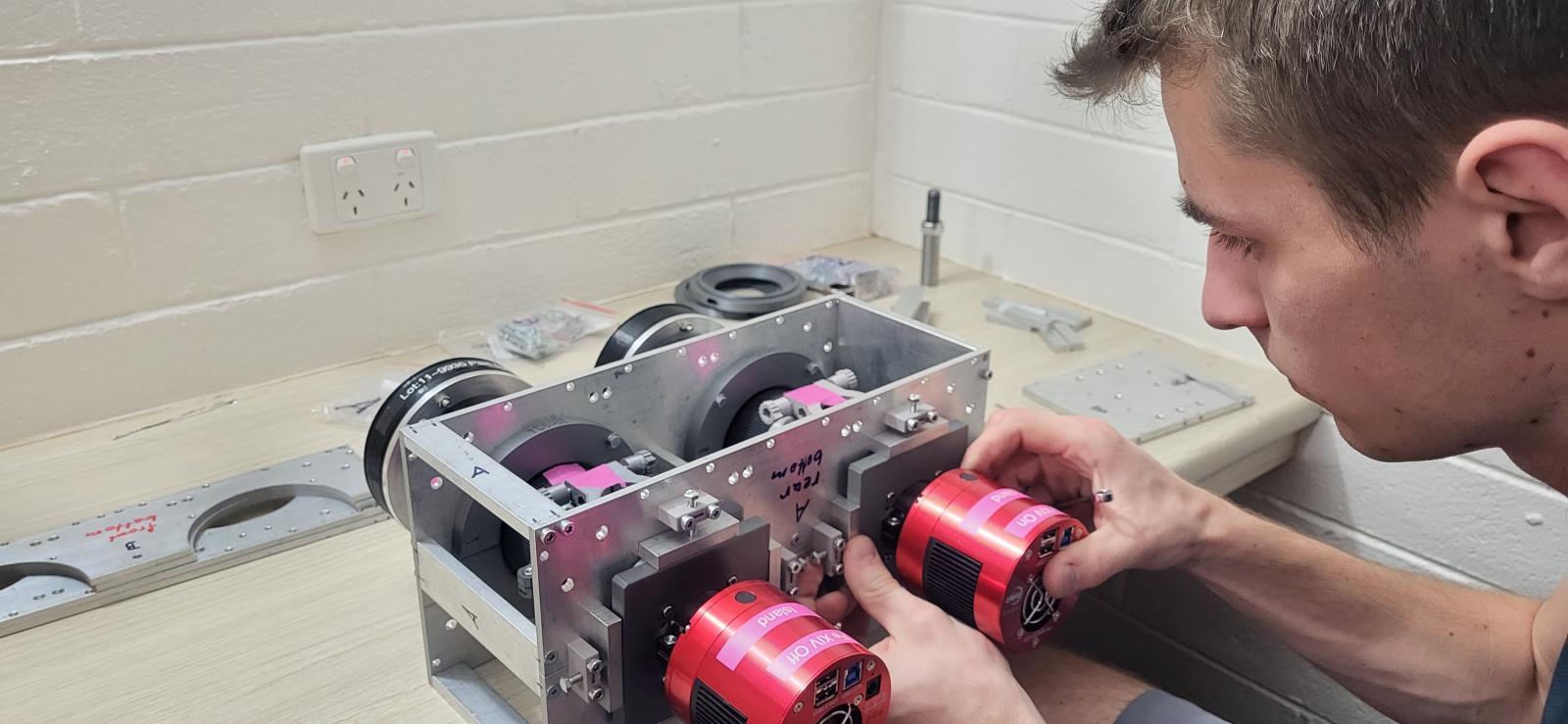

We are starting to assemble the aluminium parts we brought as a kit, 20 kilograms in total. The aluminium parts are used to assemble a holder for two optical systems for observing a single iron ion. The holders, which we familiarly call “guillotine”, can be joined together to create a variable assembly as required. Eight cameras, or four pairs, are pointed at the Learmonth site to observe four iron ions. The weight of the assembly including cameras is an impressive 25.6 kilograms.

The author of the unique design of the guillotines is Pavel Štarha. Thanks to him, working with so many cameras on one mount possible at all. Each camera can be set independently of the others to the correct position with emphasis on the resulting alignment of all cameras. Aluminium parts are complemented by parts printed on a 3D printer. We shipped one roughly three-kilogram package of plastic parts from Brno to Honolulu a month ago, printed some of the parts in Hawaii, and brought some of the parts with us. In total, seven 3D printers were involved.

In addition to assembling the guillotines, on the first day we managed to assemble three EQ5 mounts that we brought from the Czech Republic. This tends to be a traditional logistical game. How to transport all the necessary equipment plus personal belongings in two suitcases per person with a weight limit of 23 kilograms per suitcase? Another logistical hurdle awaits us before our departure to Australia. There will be nine of us leaving from Honolulu, but there will be more than eighteen bags to check in and another nine cabin bags. In any case, we always breathe a sigh of relief when we hand in our suitcases at the airport for check-in and are left with only a backpack on our backs, which we tactfully keep quiet about its weight and pretend it's like a feather when we put it in the overhead compartment in the cabin.

|

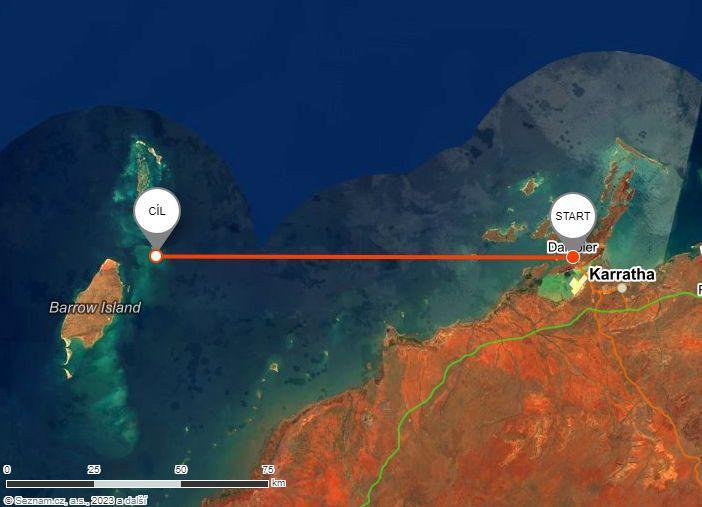

Solar Eclipse April 20, 2023 The solar eclipse of 20 April 2023 requires travel: the phenomenon will be observable in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, and will only “touch” land in Australia on the peninsula of Exmouth and nearby islands. Next, the Moon's shadow moves to East Timor and north to West Papua. Accurate eclipse information for a selected location on Earth is provided by interactive map by astronomer Xavier Jubier. The Czech-Hawaiian research team selected three observation sites: 1. Exmouth, where the eclipse will start at 11:29:48 local time and last 56 seconds. 2. Learmonth, where the eclipse will start at 11:29:21 local time and last 54 seconds. 3. Bridled Island, where the eclipse will start at 11:34:21 local time and last 63 seconds. |

Saturday 8 April

We had planned to work only half a day and then take a day off to preserve our sanity, but of course everything is different. We're catching a slip in the morning, because we're going to the Hobbymarket for substrate. What's the substrate for? We want to try to place a 25.6 kg set of eight cameras on the EQ6 mount, and we need a counterweight for that. Since it is pointless to carry weights by plane, we brought an empty tube made of waste pipe, into which a threaded rod was fixed. This tube has worked very well after filling with substrate and water.

The next activity of the day was the completion of the mount that will go to the island and will be a Nikon Z6 camera with a Maksutov 500 mm lens for white light in the solar corona. In order to make the most of the 63 seconds of eclipse time and to take as many pictures as possible with the time fan, Matěj prepared a programmable shutter that sends pulses to the camera more frequently than the commercially produced shutter with a 1 second step.

We will gradually connect the cameras to the laptops and pair them with Pavel Štarha's software. At the first connection, he found one small thing that he has to reprogram and he deals with it around midnight in his hotel room.

Sunday 9 April

Third day in Honolulu, four days until departure. It's been a terrible day. We worked all day, skipped lunch, and were done by evening. Around midnight I woke up and saw that Pavel was still working on the computer. He is aware of all the things he still has to change in the programs and no one else can do it for him. Pavel is an absolutely indispensable member of the team.

In the morning, Shadia, Adi (Adalbert Ding, emeritus professor at TU Berlin) and I spent an hour and a half discussing the placement of the individual cameras on specific mounts. Another big complication is deciding which narrowband filters to use. Pavel Štarha has primarily programmed software to control the cameras, which work synchronously in pairs to obtain an image of the distribution of a particular iron ion in the solar corona. However, the plan of colleagues from the University of Hawaii has changed and after consultation with Miloš Druckmüller, systems that are not paired but use images obtained with a different camera will be used.

The principle of two synchronized cameras working in pairs is as follows: One of the systems is tuned to the wavelength of a specific iron ion with a precision of 1 nanometre thanks to a narrowband filter. This filter is called “on band”. The filter is a cylinder with a wide base and a height of about 3 centimetres screwed to the optics, which is topped with a red camera. It seems simple – we place a filter that only allows photons of a particular wavelength to pass through and get the information we need. Unfortunately, it doesn't quite work that way. The filter has a maximum bandwidth at a given wavelength and that is exactly what is desired. But in addition, it also transmits to a limited extent all photons of the remaining wavelengths, i.e. the continuum, which spoils the pure information about the distribution of the iron ion. The second filter of the pair therefore has its filter wavelength shifted slightly, this is called “off band” and from it we get information about the continuum in the solar corona. Then we just need to subtract the “off band” image from the “on band” image and we have what we wanted: an image of the iron ion distribution in the solar corona.

In the morning meeting, however, the “on band” single systems will come into play, where the plan is to use “off band” images from other systems. This will be a challenge for Miloš Druckmüller, who processes all the data with his unique software, which he has been gradually developing and refining since 1999, and after each eclipse he has to adjust the software to the actual eclipse.

Monday 10 April

Four days to departure. We fly to Sydney on Thursday evening. The observation sites are reduced to two: Learmonth and the island. Exmouth was cancelled because it was not possible to provide facilities for our people. I deliberately write island with a small “o” because the situation is evolving every moment. Matěj and I are heading to the island and it will be a great adventure.

In Perth, we will join a group of Eclipse Chasers. This is a group that I have been to the 2020 eclipse with in Chile, so I know they are capable of anything. It's a group of gentlemen of different ages, the oldest of whom was I think 80 years old last time. They are obsessed with going to every eclipse, and then they compete to see who has spent the longest time in the Moon's shadow. And that they have accumulated a lot of minutes over the years! For one evening in Chile, one of them prepared a joking social quiz for the others with thirty questions about the eclipse. Naively, I thought I would know where everything was, but I only asked three questions out of the first ten and gave up. Seasoned matadors have even managed twenty-nine.

So we're going to spend a few days with these passionate enthusiasts. I look forward to seeing them, they are nice, non-conflicted, they all have a common goal. The choice of viewing spot is in their control, they are very reliable, they really want to see the eclipse. Up until now, Bridled Island in the Lowendal Islands has been in play, but currently the organisers have left their hands free and it will be one of the islands in this archipelago. However, they specified what boat we would be taking from the port of Dampier and the time we would be traveling: five to six hours on an open boat! We are scheduled to sail at 01:00 so that we are on a suitable island at least three hours before the eclipse. Now it's clear why no one from our group wanted to go to the island, and they chose me and Matěj as the bravest ones.

PART 2 OF THE ECLIPSE EXPEDITION SERIES

Half a ton of luggage. With such a cargo, an international scientific team from the Czech Republic and Hawaii is flying to Australia to see the solar eclipse. How do you align, package and clear so many techniques? And why sail six hours to a deserted island with a piece of equipment? Jana Hoderová, a mathematician from the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering at BUT, describes it in her travel notes.

Tuesday 11 April

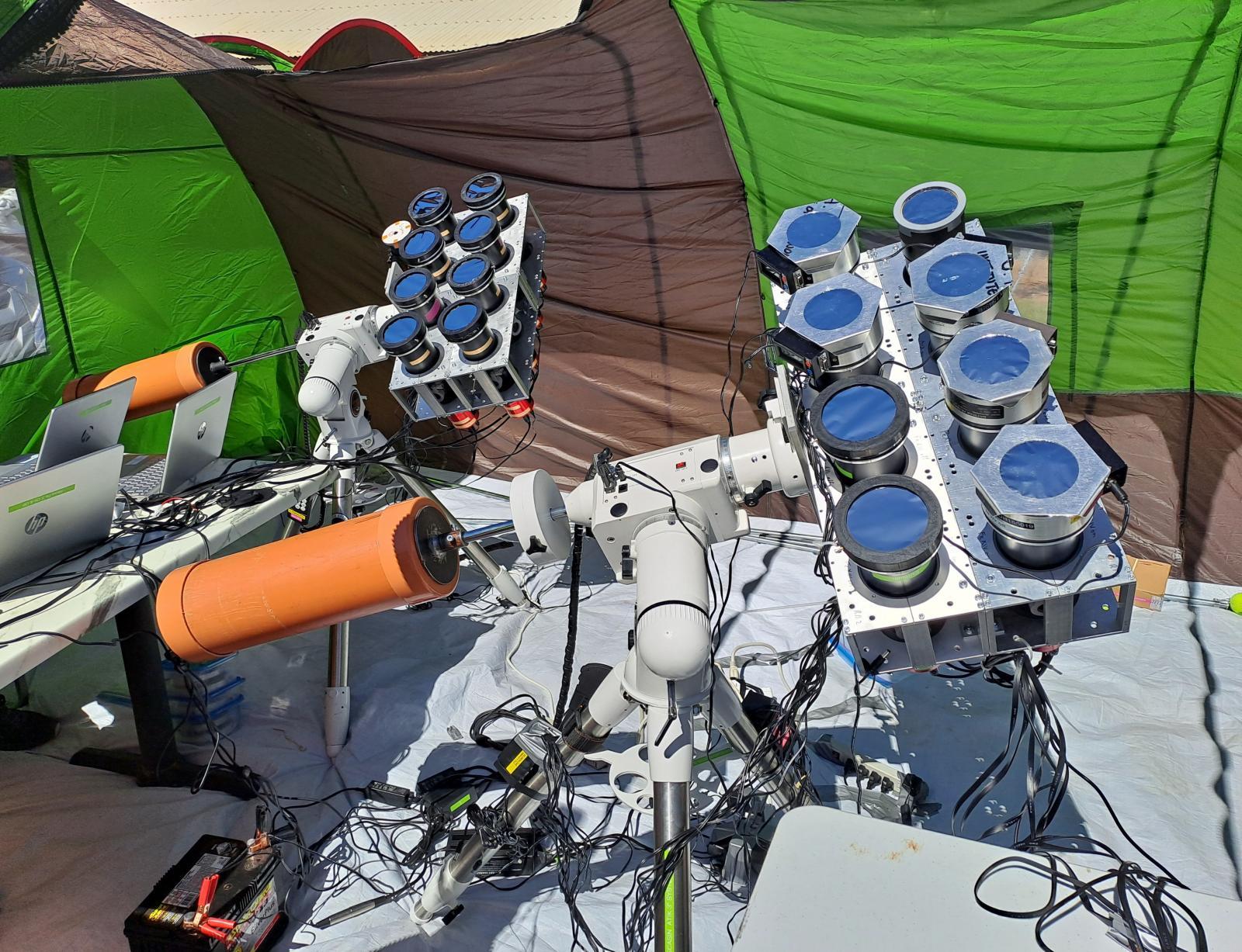

Preparations for the eclipse on April 20 are in full flow. We have reduced the number of observation points to two, but it is still a huge amount of equipment that has to be prepared and transported to the site. Almost a week ago, the University of Hawaii Astronomical Institute shipped 250 kilograms of material – three EQ6 mounts and two tents – by air freight. On two of the mounts will be the previously mentioned “guillotines”, on the third EQ6 will be the spectrometer. The other two subtler EQ5 mounts, which we carry as checked baggage, are for “white light”.

|

We see the white light with our own eyes in a darkened sky during a total eclipse. These are photons reflected from free electrons moving along the lines of force of the Sun, which is actually a giant magnet. Everyone will remember the following experiment from elementary school: take a magnet, put paper on it and pile metal filings on top. The sawdust is automatically lined up by drawing arcs on the paper that connect the north and south poles of the magnet, thus visualizing the magnetic field. In a solar eclipse, the electrons play the role of sawdust, and their negative charge forces them to follow the field lines of our day star. |

The white light image can be handled with a fairly common technique, we have two Nikon 810 cameras on the mount, both with a Nikkor 200 f2 lens and on the other mount is a Nikon Z6 II with a Maksutov 1000 mm f10 lens. Everyone is probably wondering why we use two identical cameras and two identical lenses? It's simple, the more images we get during an eclipse, the better we can process them mathematically. I recommend to look at Miloš Druckmüller's website to admire the images of the white Sun corona, for example, during the 2015 solar eclipse in Spitsbergen.

Matěj and I will bring much more modest equipment to the island, but we will still do some limited experiments that mean obtaining data at least on the most basic scale. Why are we even planning to take a six-hour open boat ride to the island if it's going to be difficult, uncomfortable and exhausting? Watching a solar eclipse is a lottery that the weather plays with us. We wish for clear skies without a cloud, but the reality is much worse and a cloud at the wrong time in the wrong place will doom the expedition to failure. So we try to have more than one observing site to increase the likelihood of getting the data we need during an eclipse. If the belt of totality across the continent goes more sensibly than this year, when Australia will be hit only very modestly in the north-west, we choose our sites according to the weather and deliberately further apart. The hope is then to observe changes in the structures in the solar corona as a function of time in the processed images.

|

The belt of totality is a strip of the Earth's surface from which a total solar eclipse can be observed. Due to the size of the Moon and its distance from Earth, its width can range from 112 to 270 km. |

In the morning we had a meeting with Miloš Druckmüller through Teams. Pavel Štarha consulted with him about the exposure times of all cameras and other details. Since Miloš will be processing all the data, he knows exactly what he needs to take down the images.

As the departure approaches, packing of equipment is becoming an issue. But you can't start without proper setup and functional testing. So Pavel carefully connects each pair of “on band” and “off band” cameras with cables to the computer, connects the camera chips to the power supply so that they can be cooled, sets the necessary parameters in his software and tests the whole prepared sequence of exposure times. It looks pretty simple now, but wait until all eight cameras are connected to the four laptops. That's just the right tangle of cables!

During the day, we were finishing the flat-field panels that we desperately need to fix the defects on the optical system. Imagine you have a speck on your camera lens, like a speck of dust. You will then have the same spot in every photo, which is not desirable. So we take flat-field images, which are one of the calibration data necessary for a good result. This means that we take seemingly homogeneous white images through the pause. However, it is the defect of the optics that is captured in these images, which we can then remove from the image we take thanks to mathematical methods. We try to have flat-field panels made on a 3D printer, but we don't have time for 3D printing of frames anymore, two printers are occupied by our colleague Adi from Berlin with his spectrometer. That's why we create flat-field panels the old-fashioned way, using paper, scissors, duct tape and rubber bands on which we put hooks made from paper clips to fix the flat-field panel in front of the lens. Sometimes we have to improvise a little.

Matěj and Pavel are still trying to see what the Nikon Z6 II can take. Here we'll be doing an exposure fan from 1/250 second to 1 second, and we need to press the shutter efficiently to get as many sequences as possible during a one-minute eclipse. In no way does this mean that we physically touch the shutter release on the camera body with our finger, that would move the camera and the images would be blurry. We have to connect the cable and pull the shutter remotely. But even that is not done manually. We need to send a request to the camera to press the shutter as often as possible to hit the most effective shot for the completed exposure fan. Commercially produced self-timer send a request every second, but we need it to be more frequent. So Matěj and Pavel made their own shutter, which are programmable and now they just have to find the minimum time interval for pressing them.

Once everything is tested, we start packing. We need to release the cameras from the guillotines, dismantle the guillotines and mounts. We have to be careful not to forget anything. The disassembly and packaging process is extremely time consuming. Today we apparently broke a record and spent an incredible 15 hours working at the university, interrupted only by a quick lunch and a slightly longer dinner. We finally got to the hotel at 01:00, totally exhausted.

For the trip to Australia, we still have to clear the technology – cameras, optical systems, lenses, laptops and more.

Wednesday 12 April

When you tell someone you're going to Hawaii, everyone dreams of palm trees, a beach and a cocktail. For us, Hawaii is synonymous with work. Packing late last night had the advantage that we are now at peace and nothing is being done at the last minute. The morning greeting with Shadia was brief: “Did you sleep?” I didn't ask the usual questions about whether she slept well, what mattered to me was whether she slept at all. She said yes, three and a half hours.

All items that must be cleared on departure from Honolulu are packed and taken to the airport. These are cabin bags, carefully packed with cameras, lenses, optical systems for observing iron ions and a spectrometer.

In any case, we will not let these cabin bags out of our sight and we will handle them very carefully. The inspectors are thorough when going through the x-ray, and when they point to an item on the list, they really want to see that thing. Fortunately, they have no desire to unscrew and separate anything from each other, perhaps due to the fact that the whole expedition is sponsored by the University of Hawaii.

We have a total of eleven cabin bags with thirty-nine items to be cleared. There are nine of us flying from Honolulu to Sydney and then on to Perth and Learmonth, or Karratha: Shadia Habbal, Ben Boe and Sage Constatinou from the Astronomical Institute of the University of Hawaii, myself, Pavel and Matěj from the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering of BUT, Adalbert Ding from TU Berlin, Eric Ayars and his doctoral student Daniell from California State University, Chico. In addition to the cabin baggage or luggage, each person has an extra suitcase or two with technology interspersed with clothing and personal items. A rough estimate of the weight of everything that will be leaving for Australia on Thursday is some 520 kilograms. And we've got 250 kilos of equipment waiting for us in Learmonth because it's been shipped in advance.

I don't think anything interesting will happen today, we're packed. But Pavel is still going full throttle and he still has some ideas running around in his head. Right now, he's sitting and thinking about an ASI camera with a 50 mm lens to capture the outer corona, structures several radii away from the Sun. It calculates exposure times to optimize the number of frames and the time the camera waits for the image to download from the chip to the computer memory. He has the idea of shooting continuously with a short exposure time instead of the planned exposure fan. In this mode, the camera stores and captures at the same time, without waiting for anything. We planned to use this idea to observe the eclipse from a ship in 2021. It was about the eclipse in Antarctica and the adjacent ocean, but unfortunately no data could be taken from on board due to bad weather. Anyway, Pavel will get in touch with Miloš and together they will discuss it.

The clearance process went smoothly, the official showed reasonable interest and let us see every single item and ticked it off the list. After returning from clearance, we were taken to the hotel. So we caught the sunset at least from the balcony of the room. We hoped that Matěj would finally see the ocean and try to experience Hawaii in a different way than just in the air-conditioned rooms of the university. A walk along the coast, albeit in the dark, lifted our spirits. And tomorrow we're flying to Australia.

PART 3 OF THE ECLIPSE EXPEDITION SERIES

Nearly eighteen more hours on planes and the international Solar Wind Sherpas science team is finally on site. At least some of them. While the main part of the expedition is already building a base on the Australian peninsula of Exmouth, mathematician Jana Hoderová and student Matěj Štarha from the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering of BUT are preparing a voyage to a deserted island 120 kilometres away. And everyone prays for a cloudless sky. Jana Hoderová describes the expedition to the solar eclipse in other travelogues.

Thursday 13 April to Sunday 16 April

These days were for the move from Honolulu to the northwest of Australia. The Honolulu-Sydney flight took 10 hours and 45 minutes, Sydney-Perth took 5 hours and Perth-Learmonth, or Karratha, where Matěj and I are going, took about 2 hours. Paul and the main group eventually ended up in Exmouth, sending his location. After investigating the originally preferred site at Learmonth, it was abandoned due to dust and wind. So Exmouth was given priority, even though crowds are expected and it will be more difficult to protect our group's facilities. Apart from the fact that people are quite naturally curious about the technical equipment, which looks quite impressive, and want to see everything really close up, we don't like having flash photos of each other in our vicinity during an eclipse.

In Exmouth, the main part of the expedition has set up two tents to house the three EQ6 mounts carried by airfreight and the two EQ5 mounts carried as normal checked baggage. The mounts will need to be carefully oriented to the south and the correct latitude of the observation point will need to be set so that in the end the motor of the mount will rotate the cameras to follow the movement of the Sun across the sky. An ordinary fixed tripod is not suitable for taking photos for further processing, because the Sun would want to “escape” from the photos during the minute eclipse. Just try to realize how fast the Sun moves across the sky. In the minute that the eclipse lasts, it will travel a path across the sky that is comparable to its radius. It may seem insignificant, but the same position of the Sun in the photo still plays a big role in the further processing of the image.

Pavel Štarha practiced again the assembly of “guillotines” and settling of optical systems. He boasted that he had now managed to place four pairs of cameras in the “guillotines” in two and a half hours, and the second set of eight more cameras took him even less time.

Before Pavel moves the mounts with guillotines and mounts with Nikon to their final location in the tent in direct sunlight, he can work in the shade and do some adjustments. They have to point the cameras so that they look at the same place, i.e. set the so-called alignment. He sent us two photos taken with two Nikon 810s with two identical 200mm lenses. According to the pictures Pavel did a good job again, as always, he has a high standard. We want to get as many such images, ideally exactly the same, as possible during the eclipse for further mathematical processing.

|

Solar eclipse is an astronomical phenomenon that occurs when the Moon comes between the Earth and the Sun, partially or completely obscuring it. Such a situation can only arise when the Moon is new. The diameter of the Sun, which is 400 times the diameter of the Moon and 400 times farther from Earth than the Moon, combined with the motion of the planets, causes the Sun, Moon and Earth to align every 12 to 18 months. A shadow a hundred kilometres wide will darken the Earth at noon, the temperature will drop several degrees. Not a sound is heard, not a bird sings. Around the Moon covering the Sun, the glow of the solar corona is visible, stars and some planets appear in the sky. |

Matěj and I stayed in downtown Perth until Monday, where we joined the Eclipse Chasers, a group I know from the 2020 eclipse in Chile. Naturally we wanted to see as much of Perth as possible before we left, as it is absolutely stunning. Modern, clean, organized – I mean, there is public transport and everything is in order.

I was quite amused when the taxi driver recommended us to go see the live kangaroos at the zoo. In the end, we were glad for the cute kangaroo sculpture in Stirling Gardens. There are more kangaroos on the Australian one-dollar coin, for example. In any case, Perth and the surrounding area would deserve many more days for a thorough tour.

Monday 17 April

After landing in Karratha, we are staying in the port town of Dampier, strategically in a hotel close to the harbour from where we will be leaving for the eclipse by boat. Matěj assembles the guillotines and solves the problem with the voltmeter, which has dropped its contact. I'm lucky he's here with me, he can handle anything.

We're already getting our stuff ready in our suitcases tonight, so that we can test the completion of mounts and setting them up to trace the movement of the Sun across the sky on Tuesday morning. In real time of the eclipse we want to try the whole prepared sequence of exposure times.

Tuesday 18 April

At eight o'clock in the morning we set up the mat in front of the hotel and prepare all the equipment as we will have it on the island. The laptops, mounts, cameras and cooling chips will be powered by battery. We have an emergency lead-acid battery with us, but luckily the hotel owner is willing to lend us his car battery, so that will be a complete safety net. It's 33 degrees, the Sun is baking, the wind is blowing quite a bit, we're topping up our fluids by the litre, the simulation of island conditions is perfect.

At the time of the eclipse, the Sun is 56 degrees above the horizon. Both montages are tracing the Sun beautifully. I have the Maksutov 500 mm f6.3 lens focused and fixed using micro focusing rings printed on a 3D printer, I went through the whole necessary sequence of steps on the Nikon Z6 II from taking pictures during 64 seconds of eclipse, through making calibration data, i.e. dark frames, flat-fields, dark-flats. Looks like I'm ready for the white light. Matěj struggles to focus the optics in the guillotines. In the afternoon, he will completely disassemble one more lens and try to find the reason why the parts cannot be rotated in relation to each other and try to focus again.

Anyway, today's six-hour training in the heat in full Sun was extremely useful. We know what we are getting into and we know that we have not underestimated anything in our preparation.

We are anxiously watching the weather forecast for Thursday's upcoming eclipse. We're glad that Cyclone Ilsa has made it out of northwestern Australia. Unfortunately, the forecast is still showing quite strong winds of around 11 m/s for the day of the eclipse in the Lowendal Islands, which is about 45 km/h. For the peninsula, where the main team with Pavel Štarha and Shadia Habbal are staying in Exmouth, the wind strength forecast is more favourable. The cloud forecast for Thursday is good so far, which is perhaps the most important thing.

|

The last total solar eclipse was observable on December 4, 2021 from Antarctica, where the Czech scientists were thwarted by bad weather. They are praying for cloudless skies even now: the whole phenomenon will last just 56 seconds in Exmouth and 64 seconds on a deserted island in the Lowendal Islands. Researchers will have their next chance a year from now, on April 8, 2024, the belt of totality will hit Mexico, the USA and Canada. The nearest total solar eclipse directly observable in Europe will occur on 12 August 2026 and can be seen in Spain or the most western tip of Iceland. The Czech Republic will not see it until October 7, 2135. |

In Dampier, we will have a test embarkation on Wednesday and a short cruise on a boat that will take us to the observation point. We will sail the ship ENRYBO KAE, its location you can follow here. Instead of the originally planned two small boats, the organizers arranged this big one. It is twenty two metres long, sails at 22 km/h, has two decks and therefore a space where a person is protected from the elements. And it has a toilet.

On the day of the eclipse, Thursday 20 April, we will take a boat to one of the islands in the Lowendal Islands, about 120 km away. Keep your fingers crossed for us.

Thursday 20 April

The day of the eclipse has come. Now the long months of preparation are finally about to come to fruition. At the main observation point in Exmouth, the rest of the group had five days to set up the mounts and adjust all the cameras. Our observation point is an island without a name, which is difficult to find on the map. Try Google satellite maps and coordinates 20.63474S, 115.57193E. You will see an island roughly 150 by 300 meters with an idyllic sandy beach on the west side.

To this island, 120 kilometres away from the port of Dampier, I am heading with Matěj Štarha in the company of twelve Eclipse Chasers, people who are literally obsessed with solar eclipses. But let's be fair: thanks to their obsession, we got the chance to have this second vantage point, even if it seemed far-fetched at first.

On Thursday we wake up at 00:30 after four hours of sleep. At 1:00 the whole group moves to the port, at 2:00 we set sail. Thanks to the training the day before, the embarkation is without any problems. Everyone is excited, the mood is optimistic, because the weather forecast is excellent, the sky is supposed to be without a single cloud. The only complication is a very strong wind from the east. The three-member crew of the twenty-two-metre ENRYBO KAE is friendly, and we will appreciate their quality and overall interplay later. We set out with the wind at our backs, the sea is relatively calm, the boat is moving smoothly, everyone is trying to sleep for a while, some on the beds in the hold, the rest on the benches around the table or on the floor. We arrive at the island at 7:15 and the captain drops anchor on the west, leeward side. Matěj and I eagerly pick the best viewing spot from the deck with our eyes.

The main organizers of the Eclipse Chaser group are going all out for us and we will be the first to land on the island. They know we're pressed for time, we need a few hours to prepare. Matěj and I thought it would be nice to start getting ready at the viewing site at least three hours before the eclipse. The crew still has to launch the small boat and do a survey to find the best place to land. We will be gradually transported from the ship to the mainland on a small motorboat with our belongings. Everything is dragging on, we are on the island at 8:45, with less than three hours left until the eclipse.

We are thinking about where exactly to place the mounts so that we are not blown away by very strong winds and the mounts are not unnecessarily leaned on during gusts. We choose an ideal spot near a three-quarter meter cliff, which will be a wonderful shelter from the wind. Unfortunately, we occasionally get hit by water splash as wind-driven waves hit the windward eastern part of the island, which is really small.

We systematically prepare everything as we have rehearsed. It was really worth training with the mounts, with attaching the cameras and guillotines, with the software. Thanks to the mock practice we manage to orient the mounts to the south, we have the right latitude and the mounts track the Sun without any problems. Of course, there is no electricity on the island. We had to import a car battery, which Matěj cleverly used to load the EQ5 mount to make it more stable against the wind.

The first contact, designated C1, the moment when the Moon appears to touch the Sun in the sky, occurred at 10:07:56 local time. Everyone looks forward to the moment, puts on special sunglasses with a solar filter and enjoys the partial eclipse lasting about an hour and a half, when the Moon slowly bites the Sun.

The partial eclipse, i.e. basically this first phase after C1, could be observed in the Czech Republic relatively recently, namely last October 25. Those who did not know that a partial eclipse was taking place did not notice anything strange. As long as, say, 99% of the Sun is not covered, it is still normally light.

As the second contact, denoted C2, approaches, the voltage rises, a lot. At that moment, the Moon slides all the way in front of the Sun and seemingly touches its opposite edge. Because the Moon's diameter in the sky is currently slightly larger than the Sun's diameter, it completely covers them. This occurs at 11:34:23 local time and that's when the real drama begins for us. The minute before, you need to take off the Sun filters that protect the chips from direct sunlight. Then we have to press the shutter button on the programmable self-timer prepared by Matěj with the utmost precision, so that the Nikon Z6 starts to make short exposures from the planned exposure fan in C2 time. The ASI cameras connected to computers are automatically started according to the time set on the computer thanks to Pavel Štarha's software. Matěj and I are all tense, each of us carefully monitoring our instruments to make sure that everything is working as it should and that there is no need to reach for an emergency scenario. Nikon Z6 is happily clicking from short exposures to long exposures and over and over again, Matěj's two monitors are displaying data about the work of four ASI cameras. Everything is running as it should! We have a few tens of seconds to enjoy this incredible phenomenon with our own eyes and take a few snapshots on our mobile phones.

It's beautiful. With the naked eye, which is capable of adjusting to the huge dynamic range, we can clearly see pinkish-purple prominences just above the surface of the Sun. In a darkened sky, white “rays” can be seen pointing away from the Sun in all directions as it is near its maximum. It is therefore not obvious at first sight where the Sun's magnetic poles are. The free electrons in its corona follow the shape of its field lines, and it is from these free electrons that sunlight is reflected, i.e. the photons that render the Sun's magnetic field for us.

The time is ticking mercilessly, 64 seconds have passed by so quickly, the diamond ring lights up violently as the third contact, marked C3, occurs. That's when the Moon pulls away from the edge of the Sun and continues to reveal itself for another hour and a half until C4 contact, when the full Sun is finally revealed. And it's over.

We're both visibly relieved. We got it, unbelievable. It worked! A huge amount of work by many people has been completed and we have obtained valuable data from the island. We stand in disbelief for a moment, looking at the cameras, stunned, and a huge relief sets in. But the work is not over, we have to take calibration images, without which further processing of images taken during the total eclipse is not possible.

|

With the acquisition of the data, the next challenging stage begins , which is processing. Here, the entire burden lies on Professor Miloslav Druckmüller. The software, which he has been developing since 1999, is able to make the most of the data by mathematically precise methods. Thanks to the details that can be seen when dozens of images are taken down, we can interpret the results together with astrophysicist Shadia Habbal, and thus gain new information about the solar corona. You can get a rough idea of what image downloading means from the following pair of images. These are white light images taken on the island with a short exposure time of 1/125 s and then with a time of 0.5 s. The short exposure time captures bright structures close to the Sun and virtually nothing is visible further from the Sun. With long exposure times, pixels close to the Sun are overexposed, but on the contrary, we see structures farther away from the Sun. |

We're done by 1:00. The Eclipse Chaser group is long packed, impatient, ready on the beach for departure. A small boat leaves the ship to pick up the first pair. And we have a problem – very strong winds and a high tide. The waves that hit the beach are huge. The motorboat tries to find a place where boarding would be possible, and on one attempted approach the wave carries the boat onto the beach. The two-man crew tries to push it into the water, but to no avail. Two gentlemen from Eclipse Chasers, Matěj and I join them and try to get the boat back in the water on some big waves. It is quite dangerous because the waves are tossing the boat in different directions and you have to dodge nimbly. But together, we did it in the end.

The crew jumped in, started the engine, drove to the boat and the waiting begins. One of the crew joined us later with a radio. Over the next two hours, the group gradually runs out of energy, you can see how tired and surprised they are by the situation. The wait paid off, however, as the next attempt by the boat crew to approach the island and board the first two survivors was successful. They had to stay more in depth and throw out even a small anchor, otherwise they would not have been able to keep the boat reasonably in one place. Matěj was the most involved, he is up to his chest in the water and holding the boat, one crew member is sitting and manoeuvring by the running engine, the other crew member is literally trying to pick up the survivors from the sea into the boat, I am shuttling between the beach and the boat and carrying their things, because it was necessary for them to have their hands free when boarding. Well, at least Matěj and I enjoyed the sea for the first time, albeit fully clothed.

We leave the island at 16:00, against the wind, against the waves. The ship is tossing me around incredibly, eventually I get totally grounded by seasickness. I bow to Matěj, he is a true sea wolf. Return to the hotel was only at 23:00, we skipped the late dinner, by 02:00 we were packing our equipment.

Friday 21 April

At 5:00 we get up, at 6:40 we leave by bus from Karratha 600 km to Exmouth, where we join the main group of the expedition with Pavel Štarha. The information from him is positive, the technique worked here too, the wind calmed down, the weather was perfect, so the originally planned long exposure times could be used. In total, they had 15 cameras for monitoring iron and argon ions, 5 cameras for white light and a camcorder for monitoring the spectrum using a diffraction grating. Observing the spectrum of the solar corona is a well-known basic experiment that we have included just for interest. We used the camcorder as a counterweight to the Nikon Z6 II with a Maksutov 1000 mm lens. Based on an initial check of the data collected, it seems that everything has been successful. In Exmouth, they obtained about 1.6 TB of data, which they backed up several times for safety.

What to say in conclusion? The eclipse in Australia 2023 was just a success. The weather turned out incredibly well, the sky was completely clear, the instruments worked, we are taking the data to Brno. Miloš, you have a lot to look forward to, you have a lot of work to do...

Author: Jana Hoderová, FME BUT

A special tribometer customised by Brno scientists for a Japanese company

Alexandra Streďanská’s fascination with fascia and hyaluronic acid

New biogas treatment technology: BUT cooperates with top European teams

Petr Viewegh’s Microcosm and Macrocosm

"Thanks to Formula, my studies make sense," says Anna Piarová, the new head of TU Brno Racing